The Flavours of our Land

As an anthropologist—a specialist in the study of cultural diversity—I have observed various agricultural practices in countries such as Mongolia, Chile, and Switzerland. Since my grandfather was raised to be totally self-sufficient, from producing his own food to crafting his own tools and clothing (for which his family grew flax), I have always been fascinated by people’s ability to produce the food and material goods they need to sustain themselves. This skill has been lost in our modern cultures, where everything is commercially available and there is no need to understand how things are made. My fascination with the know-how of people elsewhere on the planet led to my desire to connect with a local Quebec agricultural tradition; one that provides our first harvest of the year and makes us forget the harshness of our winters—maple sugaring

© Philippe Coste

In anthropology, the way we discover another culture is to live within it, as what we call a “participant observer.” Similarly, I started my exploration of the world of maple syrup by helping a friend boil down the sap from his 2,000 maple trees in the East Broughton area of Quebec. The day this friend let me load up his boiler with firewood was the day I caught “sugar fever.” And it was at that moment that I realized I would become a maple syrup producer. The intense fire, the bounty of syrup flowing through the evaporator valve, and the darkness of the surrounding night (made even more mysterious by the steam rising from the sap) transported me into a surreal universe where, strangely, I was travelling through my own culture.

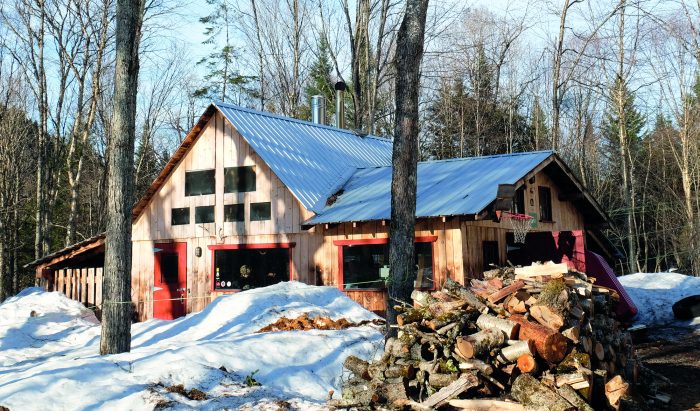

Today I own a small sugarbush in the Tewkesbury mountains, where, along with my father, family, and friends, I run my wood-fired boiler. I can no longer imagine a spring when I don’t gather sap from our maples and boil it down, and when I don’t bring together a group of people to enjoy our first group celebration of spring. This past season has reminded me that maple sugaring involves wearing 50 different hats, often flying by the seat of your pants. It’s a tough job: working in the woods to set up the tubing, getting the firewood ready, and then watching the long boiling sessions. These are definitely not insignificant chores. But you can’t put a price tag on the pride that comes from personally producing a year’s worth of sweetness for my relatives and a few other families in my social circle.

Maple sugaring brings us into a relationship with a tree that serves us in many ways by giving us woodworking material, firewood, and syrup. But beyond these uses, it has one characteristic that few trees possess: the ability to bring humans together. In northern Europe, and now to a lesser extent worldwide, the balsam fir has been doing this for centuries, as people surround it with gifts to celebrate Christmas. There’s also the baobab, which gives many African communities a place to assemble when they need to find a solution to a common problem. Here, in northeastern North America, it’s the maple that brings us together around its sugary delights, regardless of age or social class. Because sweets have the power to bring people together around an activity that’s a shared source of joy. There’s no fighting in the sugar shack!

Maple sugaring is more than just a type of farming; it’s a rich cultural experience that keeps traditions and values alive. It has its own vocabulary, its own spring rituals, and its heroes who make amazing amounts of syrup per tap. And while it stems from an ancestral tradition inherited from the First Peoples, it has also become a science, whose advances are made clear during trips to state-of-the-art boiling rooms. Making maple syrup brings together the past and the future; it’s also, quite possibly, a practice that can inspire us to find solutions to the new challenges of our time. Is harvesting sap from a sugarbush not the most graceful way of protecting nature over the long term, while still earning a living?

Since becoming a maple syrup producer, I’ve been going out to our bush much more frequently. I go there in the spring, of course, but also in the summer to plant new maples. In the fall, I wander around to collect mushrooms from the spots I noticed during sugaring season, when I found dried specimens on dead maples. I go there in winter, too, to do maple-related forestry tasks, and to harvest our lumber and firewood. With each passing sugar season, I find that the forest educates me and makes me ever more aware; it reveals its secrets while charming me with its beauty. As a result, like more and more maple syrup producers, I find that our sugarbush energizes me and makes me appreciate the role I can play in ensuring that this paradise remains accessible to future generations. And like a heroine in a Gabrielle Roy novel, I realize that maple syrup production has certainly changed my view of the forest:

“Now she saw the sugarbush gleaming in the sun! With eyes closed or open, it mattered not: everything had become visible, crystal clear. She could have said it: ‘This old tree has been giving sap steadily for six years, that one much less, and that one over there has run for only a few days every spring.’ But she could not have told what moved her most: the ground under the trees splattered with sunlight where the snow had melted and left the brown earth bare and flecked with rotting leaves, or the damp trunks of the trees themselves, with the drops of moisture glittering like morning dew…” Translated from The Tin Flute by Gabrielle Roy (tr. Hannah Josephson), 1945, p. 137.